Access Denied: ‘Āina warriors fight for the shorelineWorkshop in Lahaina focuses on solutionsMaui Time Weekly BY SYDNEY IAUKEA

A New Wave of 'Āina WarriorsA few years ago, I was approached by the HK West Maui Community Fund to help document shoreline access points in West Maui. The website Westmauibeachaccess.org was created with the information gathered. It lists West Maui's shoreline access points, maps, and photographs. The website also includes links to the cases, statutes, and ordinances that protect the public's right of way to Hawai'i's beaches and trails. A community resource such as this was long overdue, and an easy reference point for all of Hawai'i's shoreline access points was needed. No longer willing to stand by while getting squeezed out of beaches – or at least, no longer willing to remain silent about being blocked from accessing the shoreline and feeling squeezed out of beaches and the ocean – some West Maui community members and concerned citizens then created Na Papa'i Wawae 'Ula'ula informally in 2014 to protect the community's right to enjoy these places in both traditional and contemporary ways. Launching this group were community members Randy Draper, Lance Collins, Kai Nishiki, Tamara Paltin, and Autumn Ness. Na Papa'i became official in 2017, "an unincorporated association of West Maui residents and other beach users who are concerned about protecting and preserving the quality of life and environment for West Maui communities particularly as it relates to the public's use and access of the shoreline."

Working in conjunction with the West Maui Preservation Association, a nonprofit organization "dedicated to preserving, protecting, and restoring the natural and cultural environment of West Maui, its coasts, and its nearshore waters," Na Papa'i, and the various individuals listed in each of the cases, launched six lawsuits in Maui County against landowners and other entities that would in some way impede access to and limit enjoyment of West Maui's beaches. This movement to reclaim the shoreline, in practical and epistemological ways, also spawned the watchdog Facebook page called "Access Denied! Surf? Fish? Dive?" which currently has over 5,000 members online. For Randy Draper, all of this is a fitting response to his decades-long battles on Maui and elsewhere in Hawai'i – first to gain access to the shoreline and then to enforce this access for the community, which is sometimes blocked through a myriad of actions. As a longtime resident, Draper has been fighting this fight for decades and was pivotal in helping to negotiate some public spaces in the North Beach case fought in the 1990s. He, alongside other "intervenors," paved the way in practical terms for the scaling back of the mega resort plans at Keka'a, and instead fought for the inclusion of community voices in the overall development process. Their narratives, and how they helped to ignite current movements also based on past land struggles, are highlighted in my book Keka'a: The Making and Saving of North Beach West Maui. In 2017, Draper's suit against the Department of Land and Natural Resources was the first legal action taken by Na Papa'i and WMPA. Former MauiTime Editor Anthony Pignataro wrote about this case in an article headlined Maui groups sue DLNR over Ka'anapali tour boats, noting, "Draper, the hui Na Papa'i Wawae 'Ula'ula and the West Maui Preservation Association are suing DLNR over the way it currently issues permits to the many tour boats that use Ka'anapali Beach." The suit itself, Civil No. 17-1-0483(3), states that "The agents of commercial use permits have discharged refuse, sewage, or other substances likely to affect the water quality." The allegations claimed "DLNR has not prepared an environmental assessment to aid in decision-making concerning the implementation of its commercial use permitting program or project for passenger-carrying commercial ocean vessels operating out of Ka'anapali anchorage" and asserted "[Hawai'i Revised Statutes] chapter 343 procedures would have required DLNR to take a hard look at environmental impacts, including impacts to beach assess, traffic, parking, and practices of dumping sewage and other refuse in and near Ka'anapali coastal waters." The squandering of public parking was another issue: "The agents, employees, and assigns of ocean vessels operating under commercial use permits as well as their customers, utilize public parking reserved for non-commercial recreational beach users." Presently, the result of the case is that "The court ordered the parties to go into mediation, and that is where it's at now," attorney Lance Collins said. As the steward of Hawai'i's natural resources, DLNR is responsible for protecting the public from compromising these resources. According to its website, DLNR is tasked with "managing, administering and exercising control over public lands, water resources, ocean waters, navigable streams, coastal areas (except commercial harbors), minerals, and all interests herein." In contrast, the permissive permitting process and implementation of commercial ocean vessel operations possibly infringe on long-standing environmental protections. Draper remarked, "DLNR is not in the business of saving the land (and ocean), they're in the business of selling the land (and ocean)." Draper also recalled the longer historical narrative that led to litigation of shoreline access for West Maui: "Until the first group of West Maui 'Āina Warriors came to force just after Napili Plaza shopping center was built, there were about a dozen of us who didn't think it was such a great idea to have an industrial center built across the highway. Things came up like drain pipes to the nearby coves and bays in Napili, as well as noise and traffic problems, and the community stopped this. The next major community involvement was the CAC which stood for the Citizen's Advisory Committee to get the whole property zoning process to update the West Maui Community Plan, and lobby our interests to the people of Maui and the Planning Commission to help the community with more parks shoreline setbacks and affordable housing. I got asked (to participate) by Wayne Nishiki and Howard Keuhuni, both County Councilmen members, at that time knowing me from the my many times I went to them to complain about public beach access parking rights permits that were made conditions of most of the hotel building at Ka'anapali Beach. Now I can safely say the new wave social media 'Āina Warriors are here to stay and I easily feel competent YOU WILL GET THE JOB AHEAD DONE with all of you good people helping in the same common goals." Today, Draper is confident and feels reassured that there are enough people for him to pass the torch to this next generation of shoreline 'Āina Warriors. The laws are in place to protect the public's rights to access, now only reinforcement is needed for compliance.

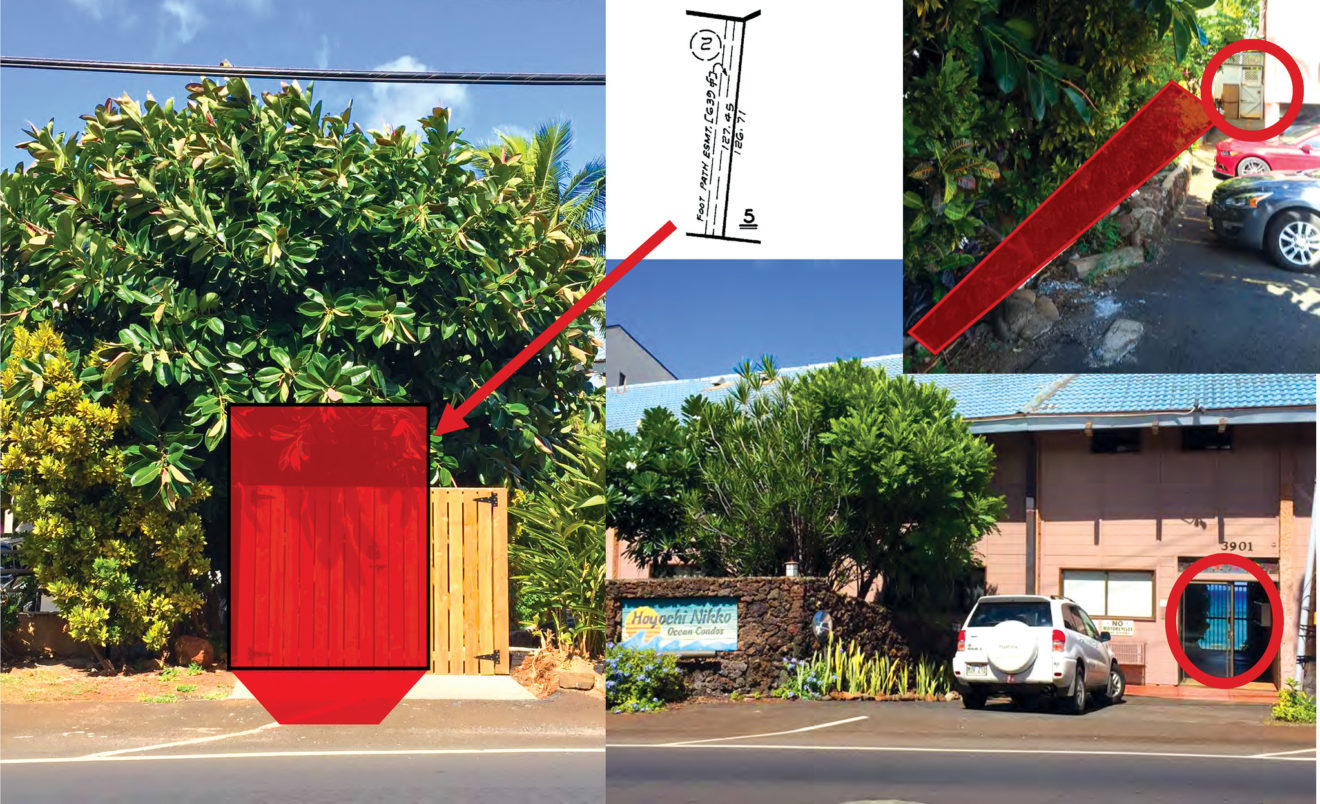

Battles for Shoreline AccessOther suits filed by Na Papa'i, WMPA, and various individuals, include litigation against the Napili II Condominiums, the Association of Apartment Owners of Hoyochi Nikko, and the Association of Apartment Owners of Hale Mahina for interfering with customary beach access rights and public rights of way to varying degrees in each case. It is noted in these suits that keeping the public from accessing the beach has the effect of hampering customary practices and stopping the continuity of fishing, diving, gathering limu, surfing, and other ocean activities by disrupting the ability to teach the keiki. We engage with the ocean to varying degrees as oceanic people. Access to these playgrounds and food sources is part of the battle to maintaining cultural identity and livelihoods. Currently, the most active court case is the Hololani seawall complaint against the Association of Apartment Owners of Hololani. To begin with, this suit alleges the Association of Apartment Owners of Hololani installed boulders and other materials without DLNR approval in 2006-2007. Since then, other materials have been added to shore up the coast, and between 2006 and 2018 a long list of allegations is claimed against the owners, the Maui Planning Department, and the Board of Land and Natural Resources. These entities, in their development goals, are also faced with rising sea levels and eroding beaches. The suit notes that "Installation of further shoreline hardening measures along Kahana Bay, including at locations fronting the Hololani Condominium and Resort would set a precedent with the potential for irreparable cultural, community, and environmental destruction." Besides the direct effect to the beach, attorney Collins explains, "these developments, which are primarily hotel and resort accommodations, were approved on the shoreline on condition that they provide shoreline access. The public has accessed to the shoreline through these properties for decades. They can't just decide one day to continue operating their hotel on the shoreline but not continue to provide access." Faced with the proposal of a 400-foot sea wall and then BLNR approval that was not upheld by the state legislature in 2018, Kai Nishiki, coordinating member of Na Papa'i testified, "Kahana has been our place to go fish, dive, collect limu, swim, surf, and enjoy time with our 'ohana. The science is clear: a huge 400 foot long seawall will destroy what we love about this place." New plans show Hololani does not intend to desist, and include the installation of a new sheet metal armoring project. However, "Shoreline hardening can cause erosion, harm reef ecosystems, fisheries, monk seals and dissipate beaches leading to the accompanying loss of lateral access." The pervading stance is that more beaches could be lost due to seawall installations.

Access is a RightAccessing the shoreline and forests is a right granted by the Hawaiian Kingdom. Historically, the Kuleana Act (1850) granted allodial title to Hawaiians and introduced fee simple land ownership to native tenants. Section 7 of the Kuleana Act granted access to resources and secured "the right of way" access, specifically stating "The springs of water, and running water, and roads shall be free to all should they need them, on all lands granted in fee simple." Or, as referred to in the Public Access Shoreline Hawai'i case in 1995, "The King responded, however, by expressing his concern that native tenants with 'a little bit of land even with allodial title, if they were cut off from all other privileges, would be of very little value… the proposition of the King, which he inserted as the seventh clause of the law, a rule for the claims of the common people to go to the mountains, and the seas attached to their own particular and exclusively, is agreed to." The PASH case summarizes, "Our examination of the relevant legal developments in Hawaiian history leads us to the conclusion that the western concept of exclusivity is not universally applicable in Hawai'i." With the legal myth of an undisturbed American jurisprudence in an occupied Hawaiian Kingdom State (sovereignty was not ceded with a joint resolution in 1898), the State of Hawai'i and the Department of Land and Natural Resources are the inheritors and interpreters of these early land laws. However, DLNR has been found at times to simultaneously uphold and disenfranchise native tenant rights. "The State," the public use doctrine reads, "has an obligation to protect, control and regulate the use of Hawaii's water resources for the benefit of its people." In 1974, Hawai'i Revised Statutes chapter 115 listed in its findings that "miles of shorelines, waters, and inland recreational areas under the jurisdiction of the State are inaccessible to the public due to the absence of public rights-of-way… and that the absence of public access to Hawaii's shorelines and inland recreational areas constitutes an infringement upon the fundamental right of free movement in public space and access to and use of coastal and inland recreational areas."

In short, "the purpose of HRS chapter 115 is to guarantee the right of public access to the sea, shorelines, and inland recreational areas, and transit along the shorelines, and to provide for the acquisition of land for the purchase and maintenance of public rights-of-way and public transit corridors." Further, DLNR and other state and county agencies, have constitutional obligations to the public trust under the Hawai'i Constitution: "For the benefit of present and future generations, the State and its political subdivisions shall conserve and protect Hawai'i's natural beauty and all natural resources, including land, air, water, minerals and energy sources, and shall promote the development and utilization of these resources in a manner consistent with their conservation and in furtherance of the self-sufficiency of the State." For decades, shoreline access was hard fought and won by surfers, fishermen, and community members. Whether this access is blocked by gates, hindered by massive amounts of hotel concession beach chairs, or a variable of other tactics meant to discourage the use of the beach, such as limiting parking or construction to shore up the shoreline, the consumerism of this basic kuleana access right, and now shoreline access right, is a fight that is both historic and marred by contemporary layers of sand claims. We see and feel these ongoing battlegrounds in the most ubiquitous ways, sometimes encountered by the simple act of going to the beach. As being in the ocean serves to connect many to their place and community in ways that are not easily measurable, these fluid spaces serve to remind us of ancestral knowing and influences our sense of being and identity. Blocking access and making it hard to get to these places is not only illegal, but it also acts as a tactic to further disposes and break connections. Feeling like outsiders trying to get to and enjoy our beaches should not be the reality. Luckily, as Draper contends, there is a whole host of 'āina warriors that are here and ready to speak up. – Sydney Lehua Iaukea holds a Ph.D. in political science with a specialty in Hawaiʻi politics. Her two book publications are The Queen and I: A Story of Dispossessions and Reconnections in Hawaii and Kekaʻa: The Making and Saving of North Beach West Maui. She is from the island of Maui, and is a dedicated community member and instructor and an avid surfer. Cover design by Darris Hurst Photos courtesy of Na Papa'i Wawae 'Ula'ula Original article URL: https://mauitime.com/news/science-and-environment/access-denied-aina-warriors-fight-for-the-shoreline/ |